The Natural Science of Feeling “At Home” in a Climate

Explore how natural science explains humans' sense of comfort and belonging within specific climates and environments.

Feeling at home in a particular climate is more than a casual preference; it represents a complex intersection of biology, psychology, and environmental science. Our natural inclination toward certain climatic conditions reflects deep-rooted adaptations and the intricate ways human physiology and cognition have evolved alongside environmental factors.

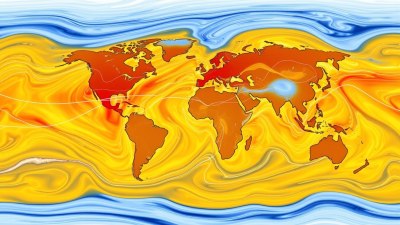

Historically, humans have migrated, settled, and thrived in diverse climatic zones, from arid deserts to lush tropical rainforests and icy polar regions. Each regional climate imposes unique demands on human survival and comfort, shaping not only our bodies but also our behaviors and cultural norms.

At the core of understanding the natural science behind feeling at home in a climate is the concept of homeostasis—a biological principle referring to the body's maintenance of stable internal conditions. Temperature regulation is a primary aspect of homeostasis, as human survival depends critically on maintaining core body temperatures within narrow limits. This regulation involves physiological mechanisms such as sweating, shivering, and vasodilation, which respond to external climate variables.

Climatic conditions also influence evolutionary traits. For instance, populations native to colder climates often exhibit traits such as shorter limbs and stockier builds, which reduce heat loss—a principle known as Allen's Rule. Conversely, individuals from hotter regions tend to have longer limbs and leaner bodies, facilitating heat dissipation. These morphological adaptations contribute to how comfortable people feel in their native or accustomed climates.

Beyond physical adaptations, cultural customs and practices are deeply intertwined with climate. Clothing styles, architectural designs, and daily routines have evolved to optimize comfort and efficiency within specific environmental contexts. For example, traditional Inuit clothing made from animal furs serves as an effective insulator against extreme cold, while cotton garments preferred in tropical climates allow for breathability and heat escape.

Psychologically, the sense of feeling at home in a climate encompasses elements of familiarity, security, and emotional well-being. Environmental psychology suggests that people develop place attachments influenced by sensory experiences such as the particular light, smells, temperatures, and sounds typical of a region. These sensory cues build a cognitive map of comfort and safety, fostering an emotional connection to the surroundings.

Moreover, climatic rhythms such as seasonal changes and daylight variations can affect human mood and behavior. Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) exemplifies how lack of sunlight during colder months can influence psychological health. As a result, populations native to higher latitudes may develop social and behavioral adaptations, including communal activities and specific diets, to mitigate these effects and maintain a balance that feels 'right' for them.

From an ecological perspective, the local flora and fauna contribute to the atmosphere of a climate, embedding an individual further into a regional identity. The presence of native plants and animals plays a role in shaping the sensory landscape, providing comfort through evolutionary familiarity. This relationship also extends to food sources, as dietary habits often align with what a climate can sustainably produce.

Technological advancements have altered the traditional relationship humans have with climate. Climate control devices such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning now allow people to artificially create environments that mimic their climates of origin. However, despite these technological buffers, many still report a deep yearning for environments that align with their physiological and psychological predispositions.

Interdisciplinary research combining anthropology, biology, and psychology has begun to elucidate how these factors coalesce to produce a sense of climatic belonging. For example, studies examining gene-environment interactions suggest that certain genetic variants prevalent in specific populations contribute to metabolic efficiency in respective climates, reinforcing the feeling of fit or discomfort in different settings.

Urban design and planning increasingly acknowledge the significance of climatic comfort in fostering social cohesion and well-being. Cities that integrate green spaces, water bodies, and climate-sensitive architecture enhance residents' sense of belonging. Conversely, environments neglecting these aspects may inadvertently generate discomfort and alienation, impacting public health.

On a global scale, climate change presents unprecedented challenges to the natural science of feeling at home in a climate. Rising temperatures, shifting weather patterns, and disrupted ecological systems threaten the stability that underpins human comfort and adaptation. Populations are facing the difficult task of adjusting to altered conditions, which may involve migration, physiological stress, and psychological strain.

Future research aims to deepen the understanding of how humans perceive and biologically respond to changing climates. Such knowledge is critical for developing adaptive strategies that support well-being in diverse environments. Integrative approaches combining wearable health technologies, environmental sensors, and psychological assessments promise advancements in personalized climate adaptation.

Understanding the natural science of feeling at home in a climate also holds implications for mental health care. Therapeutic practices and interventions may incorporate climate considerations, recognizing how environment influences emotional regulation, stress levels, and overall quality of life. Exposure therapy, for example, can be tailored to help individuals acclimate to new or changing climates over time.

Education systems are also beginning to emphasize environmental literacy to cultivate awareness of human-environment interactions. Appreciating the biological and psychological underpinnings of climatic comfort can empower individuals and communities to make informed choices in lifestyle, migration, and urban living that align with their needs.

On a philosophical level, this natural science inquiry touches on notions of identity and home. The climate is more than weather patterns; it forms part of the environmental backdrop against which culture and selfhood develop. Feeling at home, then, is an embodied experience intricately tied to place, biology, and memory.

In summary, the sense of feeling at home in a climate arises from a rich tapestry woven from physiological adaptation, cultural evolution, psychological attachment, and ecological context. It reflects the dynamic interplay between human beings and their environments, shaped over millennia of coexistence.

As cultures continue to intermingle and climates transform, the scientific exploration of this feeling deepens our appreciation for the environment's role in human life. It challenges us to foster environments that support both biological needs and emotional well-being, honoring the profound connections that make a place truly feel like home.