The Exact Chemistry That Makes Ice Slicker Than It Has Any Right to Be

Explore the precise chemical and physical reasons why ice is incredibly slick, revealing the fascinating interplay of water molecules and surface physics.

Ice is deceptively simple yet astonishingly complex, especially when it comes to its slipperiness. Anyone who has stepped onto an icy surface can attest to its treacherous slickness, but why exactly does ice feel so slippery? The slickness of ice has been a topic of scientific inquiry for centuries. Early explanations focused on melted water acting as a lubricant, but modern research delves deeper into the molecular and chemical intricacies that define this phenomenon.

At the heart of ice’s slipperiness lies the arrangement and behavior of its water molecules. Water is an extraordinary substance, exhibiting unusual properties mainly because of its molecular structure and hydrogen bonding. When water freezes into ice, molecules arrange themselves into a crystalline lattice, creating a solid with unique mechanical and chemical characteristics.

One of the foundational elements contributing to ice's slickness is the presence of a quasi-liquid layer on its surface. Despite ice being solid, the topmost molecular layer exhibits properties akin to liquid water even below freezing temperatures. This phenomenon, known as surface premelting, means that a thin film of disordered water molecules coats the ice, drastically reducing friction when an object slides across it.

The surface premelting arises because molecules at the ice surface have fewer neighboring molecules, resulting in weaker hydrogen bonding. This lack of full bonding allows molecules near the interface to vibrate more freely, causing a loosely structured layer that is more fluid-like than the solid beneath. This fluid layer can be just a few nanometers thick and dynamically changes with temperature.

Temperature plays a pivotal role in the thickness and stability of this lubricating layer. At temperatures just below 0°C (32°F), the quasi-liquid layer is thicker, enhancing slipperiness. When temperatures drop further, this layer thins and starts to solidify, reducing the ice's slickness. This explains why freshly frozen ice or ice at very low temperatures tends to be less slippery compared to ice at temperatures closer to the melting point.

Pressure also influences ice's slipperiness through a principle called pressure melting. When pressure is applied to ice, such as by the blade of an ice skate or the grip of a tire, it causes localized melting at the contact point even if the ambient temperature is below freezing. This melting produces a thin lubricating film of water, which further lowers friction and enhances glide. The pressure melting point varies inversely with pressure due to the unique phase behavior of water.

However, the pressure melting explanation fails to fully account for the slipperiness experienced on ice surfaces under minimal or no pressure, like when walking in flat-soled shoes. In such cases, frictional heating becomes important. As a foot or object rubs against ice, it generates heat at the contact interface, melting a microscopic layer of ice into water and providing lubrication. This transient layer forms and dissipates quickly, but it is crucial in sustaining low friction.

Chemically, the molecular interactions at the ice-water interface are driven by hydrogen bonds. Each water molecule can form up to four hydrogen bonds, creating a highly interconnected network. At the surface, the incomplete bonding network destabilizes the solid structure, facilitating the presence of these mobile water molecules. The bond angles and lengths in this surface layer differ from those in the bulk ice crystal, promoting higher molecular mobility.

Aside from the intrinsic structure of water molecules, impurities in ice can alter its slippery nature. Dissolved salts and organic impurities can depress the freezing point and modify the thickness and stability of the quasi-liquid layer. These contaminants can increase the liquid-like layer’s stability at lower temperatures, effectively making ice even slicker under certain conditions.

Interestingly, the molecular structure of ice itself can vary based on environmental conditions. The most common form of ice on Earth is Ice Ih, characterized by hexagonal crystals. However, other crystalline forms such as Ice Ic or high-pressure variants exist under different physical conditions. Each form has distinct lattice arrangements that influence surface dynamics and hence slipperiness.

Additionally, the roughness of the ice surface impacts how these chemical and physical factors translate to friction. Microscopically smooth ice allows the lubricating water film to spread uniformly, maximizing slipperiness. In contrast, rough, porous, or snow-covered ice can disrupt the thin film, increasing traction and reducing slickness.

Advanced spectroscopic techniques like sum-frequency generation spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy have helped elucidate the molecular details of the premelted layer. These tools measure vibrational modes and mechanical forces at the ice surface, confirming the presence and behavior of the quasi-liquid water film in real-time. Computational studies involving molecular dynamics simulations complement experimental findings by modeling hydrogen bond fluctuations and molecular mobility at various temperatures and pressures.

On a macroscopic level, the interplay of chemistry, physics, and environmental variables manifests as the characteristic friction properties of ice, which are exploited in activities such as ice skating, skiing, and snowboarding. The sharp blades of ice skates interact with the ice surface, applying focused pressure that leverages the pressure melting effect and creates a naturally lubricated interface. Skiers benefit similarly by generating frictional heat which melts the surface to allow controlled gliding.

The role of the quasi-liquid layer also explains the challenges of maintaining dry, non-slippery ice surfaces. Traditional de-icing salts work by dissolving in the surface water film and lowering its freezing point, thereby increasing the thickness of the liquid layer and improving slipperiness rather than reducing it. This counterintuitive effect means that managing ice slickness requires careful consideration of molecular-scale interactions.

Ice’s slipperiness is not merely an accident of physics but a finely balanced result of molecular chemistry, phase transitions, and surface phenomena. The intricate dance of water molecules at the interface between solid and liquid phases confers ice with its uniquely slippery nature, defying everyday intuition.

In recent years, research into artificial ice surfaces and synthetic analogs aims to harness and control slipperiness by engineering the molecular environment. By manipulating the hydrogen bonding network and surface energy, scientists hope to develop surfaces that mimic or exceed natural ice's slickness for applications in transportation, sports, and robotics.

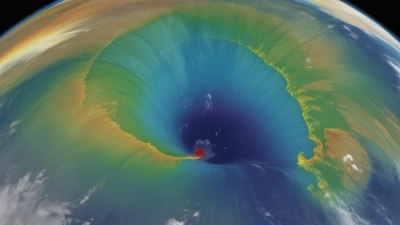

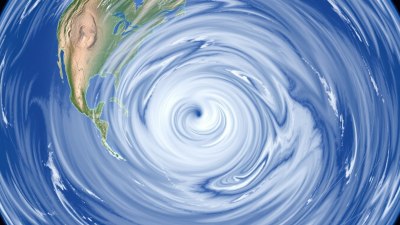

Understanding ice's slipperiness also has broader implications in climate science and planetary physics. Ice dynamics influence glacier flow, sea ice interactions, and the behavior of icy moons in the solar system. The properties of the quasi-liquid layer, molecular mobility, and impurity effects contribute to models that predict melting rates, ice creep, and other large-scale phenomena.

Summarizing the chemistry behind ice's slipperiness involves appreciating the balance between solid crystalline structure and fluid-like surface layers. Hydrogen bonding irregularities at the surface create molecular mobility that manifests as a lubricating film. External parameters including temperature, pressure, and impurities modulate this delicate state, defining the degree of slickness. From the nanoscale molecular motions to the macroscopic sliding dynamics, ice's ability to be slick 'beyond its right' is a marvel of natural chemistry and physics combined.

Future explorations will continue to unravel the precise mechanisms, refine theoretical models, and exploit ice’s slippery chemistry in technological innovations. The exact chemistry that endows ice with its remarkable slickness exemplifies how fundamental molecular interactions translate into everyday materials' characteristic physical properties.